Content brought to you by Motor Age. To subscribe click here.

What you will learn:

• "New part" doesn't necessarily mean "good" part

• Mastering tools and testing techniques eliminates self-doubt when it counts most

• Thinking outside the box is what it takes to solve many root-cause faults

What an emotional moment for a technician. We’ve all been in these shoes before: We’re near the finish line, but we realize that there are two possible outcomes ahead of us. Either we cross that finish line with our arms up in the air, and everything is perfect, or it’s not perfect, and we trip on that pothole we didn’t see. The latter can be the most frightening thing for a tech after a lengthy repair. We remembered everything, right?

It's "go" time! We’ve built up the courage. We’ve pumped ourselves up, and now we’re 100 percent confident everything is going to be just fine (Who am I kidding?). Ok, truth be told, we are not so sure. Anyways, it’s time to finally rip the band-aid off and deal with what lies ahead.

The customer’s concern

The offending suspect today is an older vehicle but had an interesting outcome. A 2003 Ford Explorer with a 4.0L SOHC (single overhead cam) engine. The customer's concern was there was a thumping noise heard under any driving conditions.

Right away, as diagnostic technicians, our minds jump to conclusions, and we’re assuming there is a suspension/tire noise, but first, we need to duplicate the customer's concern (test drive time!). My co-worker Dennis gets in the vehicle to begin his diagnosis. Right away, a loud tapping sound is heard under the hood of the vehicle. It's loud and it doesn't sound very good.

The vehicle is brought into the bay to pinpoint this noise. Without a doubt, there is a mechanical engine tapping noise coming from the driver's side valve train area. We're suspecting a crankcase ventilation baffle (in the valve cover) has broken loose and is resting/tapping on the camshaft.

Before any further testing or tear down is performed, we contact the customer to interrogate them a little further (to be 100 percent sure this noise is what they are concerned with). Remember, in the beginning, we were thinking there may be a suspension issue, right? The last thing we want to do is fix a noise they have been dealing with for years, and it not be the noise they are concerned with. Often, it can be helpful to test drive with the client to have them point out the exact noise before we begin. Unfortunately, we didn’t get that opportunity, so we decided to have a detailed conversation with them instead.

The customer agrees with what we are relaying to them. We’re confident everyone is on the same page. We then explain to the customer our suspicions (a mechanical failure within the engine is causing the issue) and advise them further tear down is needed to pinpoint the cause and correction. We need to begin by removing a valve cover to inspect, and the customer approves.

The hunt is on!

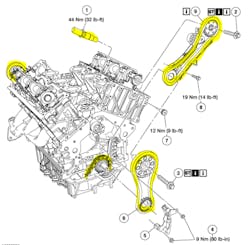

Upon removal of the valve cover, we do not see any issues with the valve cover itself or any obvious rocker arm/camshaft issues. We decide to crank the engine over (ignition disabled) with the valve cover removed to inspect the movement of the valve train components. Right away, we notice the front timing chain tensioner arm is banging against the chain (Figure 1)

The tensioner itself has completely failed and the plastic guide is moving around. This valve train setup is not a simple design, nor is it a simple repair. There are a total of four chains, including one in the back of the engine that requires engine removal to replace.

Now, I am in Northeast Ohio and directly in the heart of the snowbelt (the rust belt). Vehicles tend to deteriorate significantly faster in my area in comparison to what my friends in the south see. For a vehicle to require this extensive of a repair, it would only make sense that it be in good condition before the decision to move further is made. Turns out, this vehicle is in great condition and worth the investment. The customer decides to proceed with the repair.

There are special valve train alignment tools required to replace the chains on this vehicle (Figure 2). We order the timing chain tool kit and begin teardown. During the removal of the harmonic balancer, we find out there is damage to the outer ring where the belt would ride (Figure 3). A new harmonic balancer is ordered, to be installed during re-assembly.

After we get the front engine cover off, we notice more carnage. The balance shaft chain (the lowest chain in Figure 1) also has broken timing chain guides. The broken pieces are sitting at the bottom of the oil pan.

Now, this is a typical repair for these engines, and frankly, any overhead cam engine. These things just happen, and we see this frequently in our service centers. Dennis is chugging away and replacing these chains without an issue, up until it is time to use our new timing chain tool kit.

Square peg, round hole

Dennis calls me over to get my opinion on an issue he has noticed. The top left “Y” shaped tool (in the tool kit) is designed to lock into the crankshaft position sensor exciter ring while having its “leg” aligned with the oil pan sealing surface of the block. With everything in place, the tool is about 1/4" away from the block (Something is wrong!).

Dennis has read the repair procedure in the service manual countless times and returned to the car, scratching his head. Every step is being followed correctly. However, we still are having alignment issues. I review his steps and cannot find anything he has missed.

Now what?!

Dennis, rightfully so, chose a new aftermarket harmonic balancer to use during the installation of the timing chains on this vehicle. I would have done the same thing. I asked him to try the original balancer, just to see how it aligns with the timing chain alignment tools and new chain set. Everything aligns perfectly!

We end up putting both new and old harmonic balancers on the workbench and confirm the alignment of the crankshaft position sensor exciter ring is incorrect on the new balancer. The original balancer exciter ring is cast into the center sleeve of the balancer.

There is no way for the original balancer exciter ring to shift, as the exciter ring is part of the center sleeve. The new aftermarket balancer’s exciter ring is pressed onto the center sleeve of the balancer. Unfortunately, it has been installed a few degrees off from where it should be. Easy enough to fix, we order another one!

The second time’s the charm, or is it?

The second aftermarket harmonic balancer is in the same position as the first. Possibly, the manufacturer has an issue with the alignment procedure of the exciter ring. We’ve tried two now, and we’re not about to strike out on a third. A genuine Ford harmonic balancer is ordered. Its exciter ring alignment is exactly that of the original. Alright, let’s move on.

The rest of the timing chain replacement process goes as smoothly as possible. No other issues to be had, other than the extensive repair at hand. At the beginning of this article, I highlighted the anxiety some of us technicians face when it's finally time to start up this vehicle. We’re back to that part of the story, as the time has come!

Dennis gets in the vehicle, grabs the ignition key, closes his eyes, says a prayer to the Ford gods, and hopes for the best. The vehicle cranks and just like that, it runs! The cooling system is then bled, the fluid levels are checked; the remaining plastic trim pieces are installed, the tire pressure is checked, etc. The engine is running beautifully, and the vehicle is ready for its maiden voyage.

You thought it was over, didn't you? We’ve only just begun.

Dennis gets no further than 30' out of the door, and the engine is running terribly. There are noticeable misfires, and eventually, a check engine light is illuminated. That sinking feeling sets in (there’s that "pothole" we didn’t see).

Immediately, my mind is racing for any possibility of a simple fix, “Maybe I didn’t seat a spark plug wire in completely. Something quick and easy would be perfect right now."

The saga continues

A scan tool is used to retrieve trouble codes, and we find a P0320 – “Ignition Engine Speed Input Circuit Malfunction” (Figure 4). We notice the misfire “feels” as if it’s not cylinder specific. The engine idles well but does not want to accelerate smoothly.

A power-balance scan tool function is performed and matches our suspicions of this “misfire” not being cylinder specific. The power balance graphic is all over the place and lacks a cylinder-specific diagnostic direction. (Not a loose spark plug wire, unfortunately).

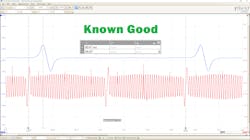

We have a crankshaft position sensor-related fault code on a vehicle we had just replaced the timing chains on, so let’s confirm the cam timing is correct. I decide to perform a cam-crank correlation test. This process requires the use of a digital storage oscilloscope and having access to a known-good waveform. Luckily, I was able to find a known-good waveform fairly quickly by browsing my archives (Figure 5).

Using PicoScopes rotational rulers, I can quickly measure (in degrees) the distance the camshaft position (CMP) sensor pulse is from the crankshaft position (CKP) sensors sync pulse. I line up the 720-degree reference marks on the CKP, and then make a quick measurement of the positioning of the CMP. This is a very fast and effective method of proving valve train timing integrity. It sure beats pulling off that timing cover again!

I do the same procedure on the vehicle we have in our bay (Figure 6). There are 66 degrees of crankshaft rotation between the CKP sync, and the first pulse of the CMP, on both captures. This proves there is not an incorrectly timed valve train assembly.

Now what?!

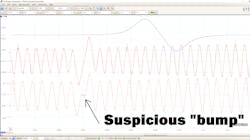

Let’s look again at the information in the code description. It states this test fails when two successive, erratic profile ignition pickup (PIP) pulses have occurred. Let’s look at that capture. I am going to zoom out a bit to see if something “erratic” happens over a longer period.

At first glance, I am not seeing something that jumps out at me as being erratic, but I do notice a small “bump” in the rising edge of the CKP’s missing tooth pulse. Let’s get a closer look at that.

I created a “reference waveform” in the PicoScope software, so I could add my suspect CKP signal to my known good. This enables me to have a single-window direct comparison of the two signals. This can be easier to identify subtle differences between the two captures (Figure 7).

What can cause this “disturbance” we are seeing? Both the CMP and CKP on this vehicle are VR (variable reluctance) style sensors. A variable reluctance sensor consists of a permanent magnet with a pole piece surrounded by a coil of wire.

This sensor simply generates an analog voltage output signal as a ferrous metal material passes across the tip of the sensor. With that, only something ferrous (magnetic) can be in the “missing tooth” section of the exciter ring. Maybe a piece of debris fell into the exciter ring during re-assembly? Let’s take a closer look.

Target acquired

Fortunately, for this vehicle, the exciter ring is exposed on the exterior of the harmonic balancer and can be easily seen without any disassembly. I asked Dennis to hop in the vehicle and "bump it over" until the exciter ring's missing tooth is exposed. I see the outer portion of the exciter ring that includes a “partial tooth” in the missing tooth section of this exciter ring (Figure 8).

Is that enough to cause our issue? In the back of my head, I could remember a post on social media for a similar scenario, but this was years ago. Remember, this is a direct-from-Ford, "OEM" harmonic balancer. This exciter ring is not the same design as the original exciter ring.

Let’s look at the original once again. We did some further investigation and noticed the Dayco brand harmonic balancer CKP exciter ring matches the design of the original. However, we cannot get one for multiple days.

Pursuing a hypothesis

After discussions with Ford and our internal management, we decide to see if removing just enough of the "partial tooth" (with a small Dremel tool) could cause this disturbance to go away. Sure enough, with just s bit of that tooth removed, our current CKP signal matches our known-good signal, exactly, and the vehicle runs like new!

All symptoms are completely gone! No trouble codes were set after multiple test drives! It’s time to call the customer and let them know their vehicle is ready to go.

As a technician, it’s situations like this that can keep you up at night. This vehicle is nearly two decades old. It’s tough to digest that “bumps in the road” like this still exist in the parts industry on a vehicle of this age. By now, “they” should have it figured out, right? Multiple issues in this story, both aftermarket and OEM, brought us in directions we wish didn’t exist. Hey, if it were easy, everyone would do it!

About the Author

Brian Culotta

Brian Culotta is a graduate of the Universal Technical Institute in Chicago, Illinois. After graduating, he started working for an independent car dealership as a lead technician for seven years. He then moved to a new job at an independent repair shop where he stayed for three years. He now works at Dave's Auto Care in Willoughby, Ohio, as the shop foreman and ASE Master L1, L3 technician.