The “Good-n-Tight” Fallacy: A Pro’s Guide to Preload and Clamping Force

Key Highlights

- Relying on 'good-n-tight' is outdated; modern repairs require precise measurement of preload and clamping force to prevent component warping and failures.

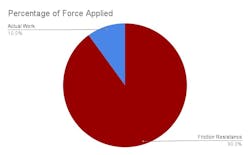

- Understanding the 90/10 rule highlights that most torque is used overcoming friction, making lubrication and cleanliness critical for accurate fastener tension.

- Calibrated tools, especially torque wrenches, are essential; regular calibration ensures measurement accuracy and consistent results.

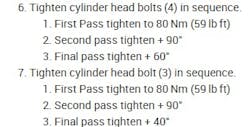

- The Torque-to-Angle (TTA) method reduces friction variability by applying a set torque followed by a specific angle of rotation, leading to more reliable fastener tension.

- Using the correct fasteners, tools, and procedures—such as TTA or Torque-to-Yield bolts—ensures repairs are done right the first time, minimizing comebacks and client dissatisfaction.

'Good-n-tight' is a phrase that costs repair shops millions in comebacks. It’s a mentality from a bygone era, and in the modern world of mixed-material engines, it's a direct route to warped components and client dissatisfaction. The 'tight enough' mentality is a fundamental misunderstanding of the purpose of a fastener. The fastener doesn’t just make things 'tight'; it provides specific forces to accomplish a task. This involves two key forces:

- Preload. The tension, or stretch, created in a bolt as it is tightened.

- Clamping Force. The equal and opposite force applied to two surfaces, created by the bolt's tension.

As technicians, we must deliver those forces precisely to ensure a quality repair—forces we cannot feel but must measure. Our hands and arms sense overall resistance but cannot distinguish between the friction of the fastener and the effort to stretch the bolt.

The 90/10 Friction Problem

One critical factor to consider is the 90/10 rule. Approximately 90% of the torque applied to a given fastener is used only to overcome friction. The remaining 10% does the actual work of stretching the fastener to apply the correct preload and clamping force for the situation. Without measurement, you are only able to feel the 90% and are guessing at the 10%. Any minor change in friction (such as a bit of rust in the threads or oil on a fastener specified as "dry") has a significant impact on the final 10%, guaranteeing a failed torque.

A Modern-Day Disaster: Mixed Materials and Human Error

Another consideration is the use of mixed materials in modern vehicles. We're dealing with plastic valve covers on aluminum heads and a cast iron block with rubber and MLS gaskets. The use of lightweight materials in parts has a significant impact on the clamping force. These parts need an even, repeatable clamping force applied to the entire surface area.

Unlike forgiving cast iron, these lightweight aluminum and plastic components will warp if the clamping force is uneven, which can lead to a leak. Relying on perception over calibrated tools is often a matter of guesswork, resulting in poor outcomes. 'Tight enough' at the start of the week rarely matches 'tight enough' after days of fatigue. The feel of a fastener in one position can be different than the feel of a fastener that is in a different position or at an awkward angle. A ¼-inch ratchet will feel different than a ½-inch ratchet. A precisely calibrated digital torque wrench is repeatable and measurable.

In a modern repair facility, clients expect repairs to be done right the first time. Consistently following torque specifications and sequences not only prevents costly rework but also ensures peace of mind for both technicians and clients. The key is to prioritize accuracy in every repair to maintain trust and efficiency.

The Pro's Guide: From "Feel" to "Fact"

Now that we understand the fallacy, how do we move from "feel" to a professional, repeatable process? It comes down to actively controlling the variables that "good-n-tight" ignores.

1. Control Friction: The "Wet vs. Dry" Factor

Since friction is the 90% variable, it is the first and most critical one that a technician must control. Every torque specification is engineered for a specific coefficient of friction. This means the engineer's calculation assumes the threads are either "dry" or "wet" with a specific lubricant.

- Disaster Scenario 1 (Over-torque). A technician sees a "dry" spec but decides to apply a small amount of anti-seize or oil to the bolt to "help it." The friction plummets. When the wrench clicks at 80 ft-lbs, that 10% of "stretch" is now 40% or 50%. This yields the bolt, strips the threads, or, in the worst-case scenario, cracks the component.

- Disaster Scenario 2 (Under-torque). A "wet" spec calls for bolts to be dipped in 30-weight oil. Tech installs them dry to avoid a mess. Friction spikes. The 80 ft-lbs "click" is achieved, but 99% of that torque was lost to friction. Almost no preload is achieved. This guarantees a leak or a loosened fastener down the road.

The Pro's Process: Always start by cleaning threads with a thread chaser (which reforms threads, not a tap, which cuts new material). Visually inspect the threads for damage. Then, apply the exact lubrication specified by the OEM, or install the fastener perfectly clean and dry, as the procedure dictates.

2. Control the Tool: The Calibration Factor

With the friction variable controlled, the next step is to ensure the tool itself is correct. A torque wrench is a measuring instrument, not just a ratchet. Using an uncalibrated torque wrench is just a more expensive way of guessing. All types of wrenches—beam, click, and digital—drift over time. Click-type wrenches are especially sensitive. Dropping one on the floor or storing it with the spring under tension (i.e., not wound back to its resting position) can create an immediate error. Your torque wrench must undergo regular calibration (at least annually, or as per your shop's quality-control policy). Always store click-type wrenches at their lowest setting to relax the spring.

3. Control the Method: Why TTA is King

Finally, engineers are fully aware of the friction problem. Their solution, which is now standard on most modern engines, is the Torque-to-Angle method. It is designed specifically to eliminate the friction variable.

The TTA process is simple:

- Seating Torque. A low initial torque (e.g., 25 ft-lbs) is applied. This snugly secures the components and aligns all fasteners to a uniform, friction-overcoming starting line.

- Angle of Rotation. A specific degree of rotation (e.g., "plus 90 degrees") is then applied.

This method is superior because once the fastener is seated, the angle of rotation has a direct, physical relationship with the bolt's pitch and stretch. Turning that bolt 90 degrees will stretch it by a highly predictable amount, regardless of whether the threads are slightly oily or slightly dry. It takes the guesswork out. This TTA method is often paired with Torque-to-Yield bolts. These fasteners are designed to provide a uniquely high and consistent clamping force by being stretched once into their "plastic" (yield) zone. This permanent stretch is precisely why they are single-use. Reusing a TTY bolt guarantees poor clamping; it's permanently stretched and can't be secured again.

The Pro's Process. Always have the right tools before you start the job. If a procedure specifies TTA, a simple torque wrench is insufficient—you must have an angle gauge or a digital torque-angle wrench. If the procedure calls for TTY bolts, you must have a new set on hand. Attempting the job without the correct, specified fasteners and tools is no different than guessing.

From 'Tight' to 'Correct'

At the end of the day, we have a duty to our clients to repair their vehicles professionally and without comebacks. Relying on feeling alone for tightening is focusing on input and ignoring the outcome. We owe it to ourselves and our clients to ensure the outcome is a securely fastened part and a reliable repair. Stop guessing and start knowing.

About the Author

Noah Nelson

Technical Editor | Motor Age

Noah Nelson serves as Technical Editor for Motor Age. His 20+ year career began as a lube technician and evolved through the ranks to district management. Now an ASE Master Technician, Noah leverages his diverse background to provide the industry with practical, real-world technical insights.